|

Audio: Listen to this post | © ClassicBooks.com

|

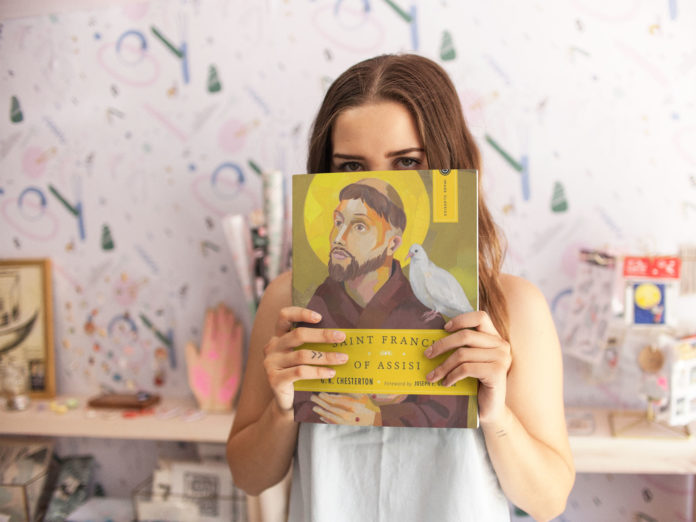

St. Francis of Assisi by G. K. Chesterton nears perfection in appreciating Francis’s multifaceted life. Francis of Assisi is one of the greatest saints in the Christian calendar, which explains why he attracted the attention of legendary authors like G. K. Chesterton. This biography views Francis as a paradoxical figure, a man loved by women but who decides to live a life of chastity. Whereas he loves the pleasures of the world as all people do, he vows to the most austere poverty. St. Francis of Assisi by G. K. Chesterton is just 199 pages but requires a focused reading to grasp not only the rationale behind this biography but also the dense vocabulary used by the author.

Introduction

St. Francis of Assisi tells the story of a man who is courageous enough to respond to God’s calling and who is ambitious to take arms and pursue honor. The challenges faced by St. Francis back then are very similar to those in our modern generation. He tried to put a stop to the Crusades by converting to Islam but did not get the desired results. He did not have a relationship with his father since he stole countless bales of his father’s clothes and sold them. This led to his father persecuting him, and Francis lost moral authority in society. As much as he faced countless adversaries, yet he stood firm and entered into fasting and vigil. Reading this book inspires the ideals of perseverance, determination, and the urge to live by God’s desire.

St. Augustine Biography

Saint Augustine of Hippo was born on November 13, 354, in the town of Thagaste, on the northern coast of Africa, in what is now Algeria. North Africa was part of the Roman Empire, though it was considered something of a backwater, far from the centers of imperial power. Augustine’s father, Patricius (or Patrick), was a decurio, a minor official of the Roman empire. The position was far from glamorous, however, because a decurio was required to act as a patron for his community and to make up any shortfalls in taxes collected from the region. This responsibility probably kept a constant strain on the family’s finances and may account for Augustine’s assertions that his family was poor. Augustine had at least one brother, Navigius, and at least one sister, but little information is available about his siblings.

Patricius was a pagan, an adherent of the Roman civic religion. Augustine’s mother, Monica (sometimes spelled Monnica), had been raised as a Christian. Although Patricius was only lukewarm about Christianity, he allowed Monica to raise the couple’s children as Christians, and he finally converted to Christianity before his death. The example of his mother’s fervent faith was a strong influence on young Augustine, one that would follow him throughout his life. In contrast, Patricius had relatively little influence on Augustine’s character, and Patricius appears in The Confessions as a distant and vague figure.

Augustine showed early promise in school and, consequently, his parents scrimped and saved to buy their son a good Roman education, in the hope of ensuring him a prosperous career. He was sent to the nearby town of Madaura for further studies, but a lack of money forced him back home to Thagaste for a year, while his father tried to save more money for tuition. Augustine describes himself as a dissolute young man, unrestrained by his parents, who were more concerned with his success in school than his personal behavior.

When Augustine was about 16, his parents sent him to the university at Carthage, the largest city in the region. There he studied literature and poetry, in preparation for a career as a rhetor, a professional public speaker, and a teacher of rhetoric. Soon after Augustine came to Carthage, his father died, leaving Augustine as the nominal head of the family. In Carthage, he set up a household with a concubine, the mother of his son, Adeodatus, born about 372. During this period, he read the book that began his spiritual journey: Cicero’s Hortensius, which he says inspired him with the desire to seek the truth, in whatever form he might find it. In Carthage, Augustine also encountered Manichaeism, the religion that dominated his life for the following decade. Augustine was attracted to Manichaeism’s clear dividing line between good and evil, its highly intellectual mythology, and its strict moral standards.

After Augustine finished his studies, he briefly returned to Thagaste to teach, but soon went back to Carthage, where opportunities were more plentiful. Augustine became a successful public speaker and teacher. Encouraged by wealthy Manichee friends, he moved on to Rome in 383, hoping to advance his career. Rome proved to be disappointing, but Augustine’s talents caught the eye of a Roman official who recommended Augustine for the position of public orator for the imperial city of Milan.

In 384, Augustine moved to Milan, where he heard the preaching of Bishop Ambrose. Augustine had always considered Christianity intellectually lacking, but Ambrose’s application of Neo-Platonic ideas to the interpretation of Christian scripture, presented with Ambrose’s famous eloquence, captured Augustine’s interest. Augustine had been growing steadily dissatisfied with Manichaeism, and Ambrose’s influence encouraged him to make a break with the Manichees. Augustine read the works of the Neo-Platonists himself, and this reading revolutionized his understanding of Christianity. Meanwhile, Augustine’s career was flourishing, and his worldly prospects were bright.

His mother had followed him to Milan, and she arranged an advantageous marriage to a Christian girl from a good family, requiring Augustine to send his concubine away. In the fall of 386, he had a conversion experience that convinced him to renounce his career and his marriage prospects in order to dedicate his life to God. He spent the winter with a group of like-minded friends, withdrawn from the world, reading and discussing Christianity. At Easter 387, he was finally baptized by Bishop Ambrose. On their way back to Africa, his group of friends and family was delayed in the coastal city of Ostia, where Monica fell ill and died. The account of Augustine’s life as set out in The Confessions ended when Augustine was about 35 years old, but his life’s work was only beginning.

In 389, Augustine returned to Thagaste, where he lived on his family estate in a small, quasi-monastic community. But Augustine’s talents continued to attract attention. In 391, he visited the city of Hippo Regius, about 60 miles from Thagaste, in order to start a monastery, but he ended up being drafted into the priesthood by a Christian congregation there. In 395, he became the bishop of Hippo. He spent the next 35 years preaching, celebrating mass, resolving local disputes, and ministering to his congregation. He continued to write, and he became famous throughout the Christian world for his role in several controversies.

During this period, the Christian church in North Africa was divided into two opposing factions, the Donatists and the Catholics. In the early 300s, the African church had suffered Imperial persecutions, and some Christians had publicly renounced their beliefs to escape torture and execution, while others accepted martyrdom for their faith. After the persecutions ended, the Catholics re-admitted those Christians who made public repentance for having renounced their faith. But the Donatists insisted that anyone wanting to rejoin the church would have to rebaptized. Furthermore, they refused to recognize any priests or bishops except their own, believing that the Catholic bishops had been ordained by traitors.

By the 390s, the conflict had erupted into violence, with Donatist outlaws attacking Catholic travelers in the countryside. At first, Augustine tried diplomacy with the Donatists, but they refused his overtures, and he came to support the use of force against them. The Roman government banned Donatism in 405, but conflict continued until 411 when hundreds of Donatist and Catholic bishops met for a hearing in Carthage before the imperial commissioner Marcellinus, Augustine’s friend, and a Catholic. Augustine, the former rhetor, eloquently argued the position of the Catholics, and Marcellinus decided in their favor. Donatism was suppressed by severe legal penalties. Augustine’s vision of Catholicism as an institution that could thrive despite the imperfections of believers later became a definitive statement about the role and purpose of the church.

While the Donatist controversy was in full swing, a catastrophe struck the Roman world. In the year 410, Rome, the symbolic capitol of an empire that had dominated the known world for hundreds of years, was looted and burned by the armies of the Visigoths, northern European barbarian tribes. Many people throughout the empire believed that the fall of Rome marked the end of civilization as they knew it. In response, Augustine began writing his greatest masterpiece, The City of God Against the Pagans, which he worked on for 15 years. In The City of God, Augustine places the heavenly and eternal Jerusalem, the true home of all Christians, against the transitory worldly power represented by Rome, and in doing so, he articulates an entirely new Christian world view.

About the time of the fall of Rome, a movement called Pelagianism began in the church, calling for a fundamental renewal of spiritual and physical discipline. Its founder, a British monk named Pelagius, had read Augustine’s plea to God in The Confessions, “Grant what you command and command what you will” (10.29). Pelagius was horrified by the apparent human helplessness that Augustine’s statement seemed to imply. If human beings were incapable of being good without God’s assistance, then what use was a human free will? Pelagius argued that human beings could choose to achieve moral perfection through sheer force of will — and not only that they could, but that they must. Augustine, on the other hand, argued that no human being could expect to achieve anything like moral perfection; the human will was irrevocably tainted by original sin. Christians could and should strive toward goodness, but they must also recognize their fallen state and their dependence upon the grace of God.

Once again, Augustine presented the argument that won: Pelagius was officially condemned in 416 and sent into exile. But Pelagianism remained influential, and Augustine spent his final years locked in a long-distance debate with an intelligent and articulate advocate of Pelagianism, Julian of Eclanum. Among other matters, Augustine and Julian clashed on the nature of human sexuality. Augustine identified the beginning of sexual desire with the beginning of human disobedience, Adam and Eve’s original sin that tainted all humankind. Julian, however, could not accept the idea of original sin. He insisted that sexual desire was simply another of the bodily senses and that the justice of God would not inflict punishment on the entire human race for the disobedience of one person.

In his debates with the Pelagians, Augustine broached another difficult issue, that of predestination. Because Augustine had argued that only the grace of God could move human beings toward salvation, the issue of how God chose those who would be saved became paramount. Augustine asserted that only a few people were saved, and only God knew who was saved and who was not. This assertion provoked a sort of revolt among several French monastic communities during 428. If one could undertake heroic acts of self-denial and spiritual commitment, as the monks had done, but still not know if one was saved, then what was the point of trying? In response to letters from the monks, Augustine acknowledged that predestination was a difficult issue, but he refused to yield the point. Predestination did not mean that human beings could safely give up spiritual striving; perseverance in faith was one of God’s gifts to human beings.

In 429, North Africa was invaded by the Vandals, another barbarian tribe from Europe. The Vandals besieged the city of Hippo during the summer of 430; Augustine fell ill during August. According to his biographer, Possidius, Augustine spent the last days of his life studying the penitential psalms, which he had posted on the walls of his room and weeping over his sins. He demanded that no one visit him, giving him uninterrupted time to pray. Augustine died on August 28, 430, at the age of 75, so he did not live to see the Vandals overrun Hippo in 431. The world Augustine had known, the old Roman Empire that had educated him even while he deplored it, was genuinely coming to an end. Augustine had an enormously influential role in shaping the world that replaced it, the Christianized civilization of Medieval Europe.

Major Works

Augustine was a prolific writer, producing more than 300 sermons, 500 letters, and numerous other works on a wide variety of topics. Many of these works have yet to be translated into English, although a massive translation project is currently underway. Conscious that he was leaving behind a large and influential body of work, Augustine set about organizing and revisiting his writings toward the end of his life, in his Retractiones (Retractions, 427). Although he never completed this task, his work and that of his friend and biographer, Possidius, left future readers with a well-documented list of Augustine’s works.

Besides The Confessions (written 397-401), Augustine’s other great classic work is De civitate Dei or The City of God (written 413-427), a monumental exploration of the end of pagan civilization and the role of Christianity in history.

The problem of St. Francis

G. K. Chesterton acknowledges that St. Francis was a difficult man to analyze. The approach with which one decides to have a look at him can be from three different dimensions. The one that the author adopts is the most difficult, and it needs an open mind to fully understand.

For starters, St. Francis is a great figure in secular history while at the same time highly admired based on his social virtues. Some even consider him the world’s most sincere democrat. “All those things that nobody understood before Wordsworth were familiar to St. Francis. All those things that were first discovered by Tolstoy had been taken for granted by St. Francis.” With all these inter-mixing of virtues, it can be quite hard to attribute where he actually belongs. That is why Chesterton does an impressive job of trying to help us understand who the man was.

St. Francis had the tendency of going to the extreme opposite and becoming defiantly devotional. In this regard, his interest would be to consider religion as the real thing. The author focuses on what it would be like to be the real St. Francis of Assisi. He would be able to find austere joy while exposing paradoxes of asceticism.

The World St. Francis found

Francis did not find a perfect world. Rather, it was marred with eventualities which clearly do not anchor well with Chesterton. One gets the impression that the author had strong negative emotions about modernism. He considers modern innovation to have been a bad thing as it “Substitutes journalism for history.” Instead of focusing on the whole story, modernism makes us eager to hear the last chapter of the story, “when the hero and heroine are about to embrace.” Even though the innovations of that time were not anything close to what we have today, these remarks hold.

Just like journalism suffers from its own imperfections, so does most modern history. Rather than going deeper into Christendom, it only dwells on the basics, telling half of the story and leaving the other half unexplained. Chesterton notes that those whose religion starts with Reformation are not best suited to account for anything since they will be dealing with institutions that they do not know their origin.

Some people may find it means to describe the world or universe so as to describe a man. This would mean that descriptions of the universe would revolve around the man. However, that is not the case in this book. As a matter of fact, the essence is to paint the picture of a very small figure under the vast sky. In so doing, one is best positioned to venture into the life of St. Francis of Assisi.

Francis the fighter

The book refers to a tale of how Francis ended up getting his name. According to this tale, the Saint had an ordinary name. His friends often called him Frenchy, The Little Frenchman, or Francesco. However, his birth name was John, given to him in the absence of his father, who was in France. Upon his return from France, after a successful commercial trip, he was filled with so much enthusiasm for the country that he gave his son the new name, signifying Frank. This name has a meaning, given that it connects Francis with himself.

No one doubted Francis Bernardone’s courage of heart, even from the military and manly perspective. A time came when his courage was put to test on matters of holiness and grace of God. But if there was one thing that he never compromised on was punctiliousness. The humble man had high regard for good manners, something we all can also learn from.

Francis’ courage was not just portrayed in terms of strength. It is also reflected in his personality. The book references another story Francis encountered. At one point, while strolling in the market, he comes across two talkers – merchant and beggar. Torn between listening to both of them, he chooses to first finish his business with the merchant. By the time he was done, he had found the beggar had gone. At an instant, Francis raced across the marketplace, looking for the beggar, unprotected. Still running, he looked around the crooked streets in search of his beggar whom he found and gave good sum money. At that very moment, he swore to God that he would never fail to help a beggar.

Earlier biographers of Francis, largely influenced by religious revolution, often talked about the man from the perspective of omens and signs of spiritual earthquake. This book is written from a more objective perspective. It does not seek to decrease the dramatic effect. Rather, it increases it when it realizes anything mystical about the young man.

The Three Orders

Three is a term that often signifies finality while at the same time, it has a lot of significance attached to it. Procession of history proves this. For instance, The Three Soldiers of Kipling and The Three Musketeers.

A discussion on St. Francis would be incomplete without mentioning the Three Orders. Also called Franciscans, The Three Orders are interrelated mendicant religious orders in the Catholic Church that Saint Francis of Assisi found in 1209. They are the Order of Friars Minor, the Order of Saint Clare, and the Third Order of Saint Francis.

These Orders adhere to the teachings established by the founder like Elizabeth of Hungary, Anthony of Padua, and Clare of Assisi. This book is a great way to learn more about these orders. It tells of how Francis set out on a mission to get approval from Pope Innocent III to form a new religious order, out of determination and passion for Christ, achieved the ambition.

Conclusion

As you come towards the end of this review, you might be wondering how the story of Francis helps you counter the challenges in your life. One thing that you could take from the book is an individual’s determination to be a person of action. Even as you do so, you still ought not to lose your sense of humor and the ability to approach life with caution.

One could simply state that what made St. Francis of Assisi keep moving forward was the concentration on God’s will. It’s true that he had visions that showed him the right path to take, but what’s more important was the determination to keep moving forward in spite of the disappointments and failures. If you cannot run, walk; if you cannot walk, crawl; in whatever you do, make sure that you are moving. This is a powerful message that G. K. Chesterton clearly passes across in this biography.